Editor’s note: Making end-of-life decisions for another person can be among the most difficult, emotionally charged choices made by family members and medical personnel. In this series, Covenant hospital chaplains share their experiences of walking with others and how they have been impacted. For related stories, see A Holy Presence and Sacramental Tears.

MISSION, CA (May 2, 2016) — Helping individuals and families make end-of-life decisions in a crisis is difficult in any scenario, but it can be even more turbulent when surrogates and physicians disagree on the best course of action.

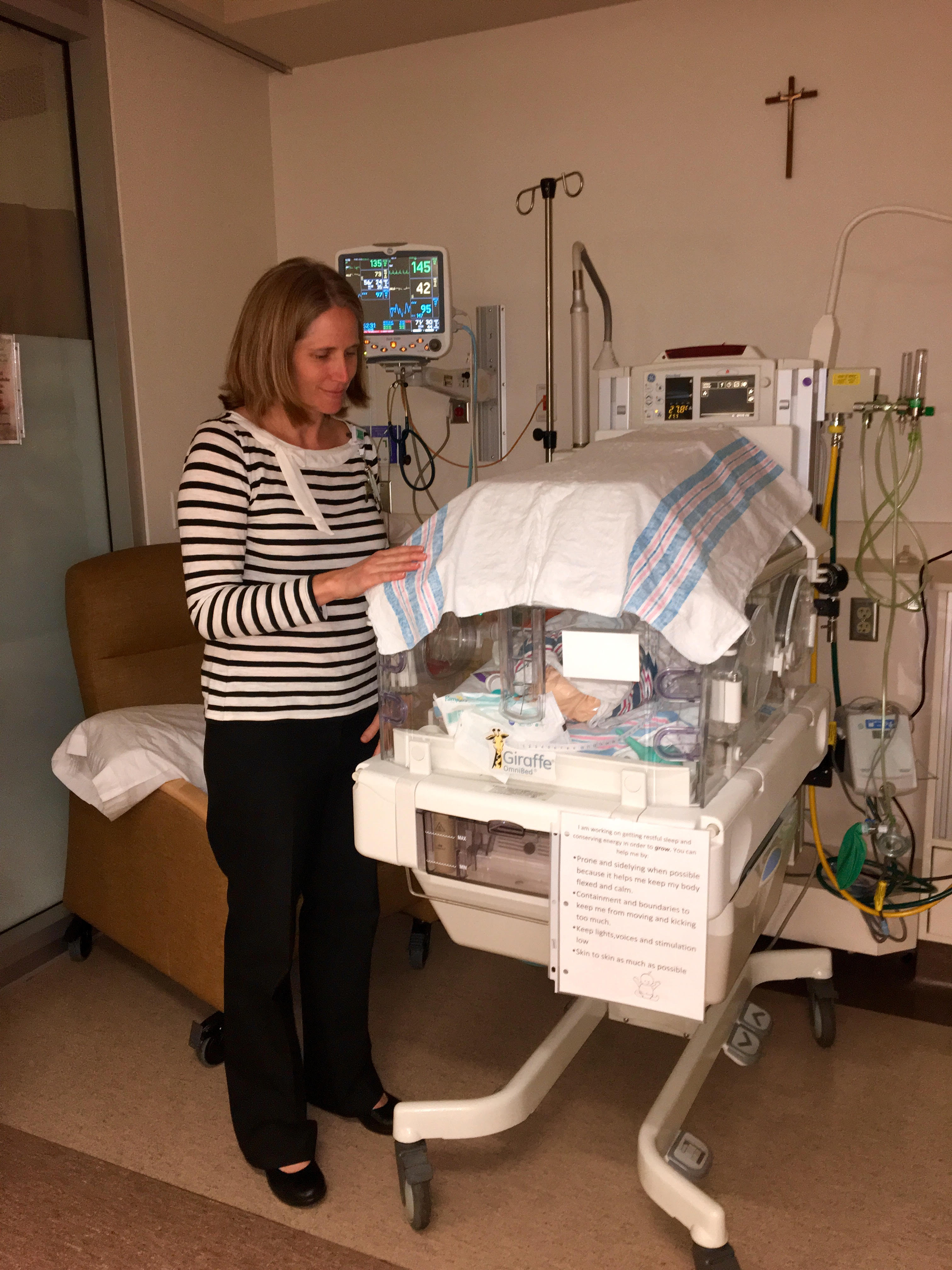

Covenant hospital chaplain Kristin Michealsen seeks to support both perspectives.

Covenant hospital chaplain Kristin Michealsen seeks to support both perspectives.

“My first go-to is with the families,” Michealsen says, “I think part of my role is always to remind the medical professionals that this is a person, this is a family—to remind them of the human and spiritual side of things.”

Often family members are trying to make what may be irreversible decisions amid the competing emotions of grief, anger, fear, guilt, anxiety, depression, love, and their own sense of right and wrong.

“They don’t want to make a decision in which they feel like they are causing their family member to die even when there are a ton of factors contributing to the patient’s poor prognosis,” Michealsen says. They also don’t want to make a decision that could cause their family member to suffer.

“We talk about it a lot here in the hospital,” Michealsen says. “What does quality of life mean to you? My standard for quality of life might be different than yours.”

According to a study in the Annals of Internal Medicine, one in three surrogates will carry a lasting emotional burden about their decision, struggling with anxiety and depression. Decisions makers, especially those who have provided long-term care for the patient, have a significant risk of post-traumatic stress disorder.

Amid the crisis, sometimes family members feel that the physicians are concerned only with clinical facts and probabilities. But that’s not necessarily the case. Sometimes medical professionals are concerned that the family’s requests will actually cause more suffering for the patient, Michealsen says. In such cases, physicians are limited in their ability to help the patient. “That’s a very real thing for caregivers in a clinical setting,” she says.

A University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine study found that the words doctors use can have a significant bearing on choices made by surrogates and how they felt about them later.

Michealsen says she tries to help physicians communicate with families. “I have a lot of discussions with them and ask, ‘Can you frame that question in a different way?’ ”

Categories:

News

My husband passed away from mixed dementia (Alzheimer’s and Vascular Dementia). We had hospice in our home at the end of my husband’s life. Hospice moved a hospital bed into our bedroom and I slept next to him. Our dog would travel between our two beds–much comfort to my husband.

Hospice were wonderful. It was hard to administer morphine to him every four hours knowing what was coming. But I have no regrets because I was there–until “death us do part.” He knew me and the last thing I said to him was, “I love you, the Lord loves you and has prepared a place for you, it’s okay to go there and I will be okay.”

A beautiful reflection on the sacredness of the lived experience of your marriage vows. Thank you for sharing Carol, and I’m sorry about your loss.